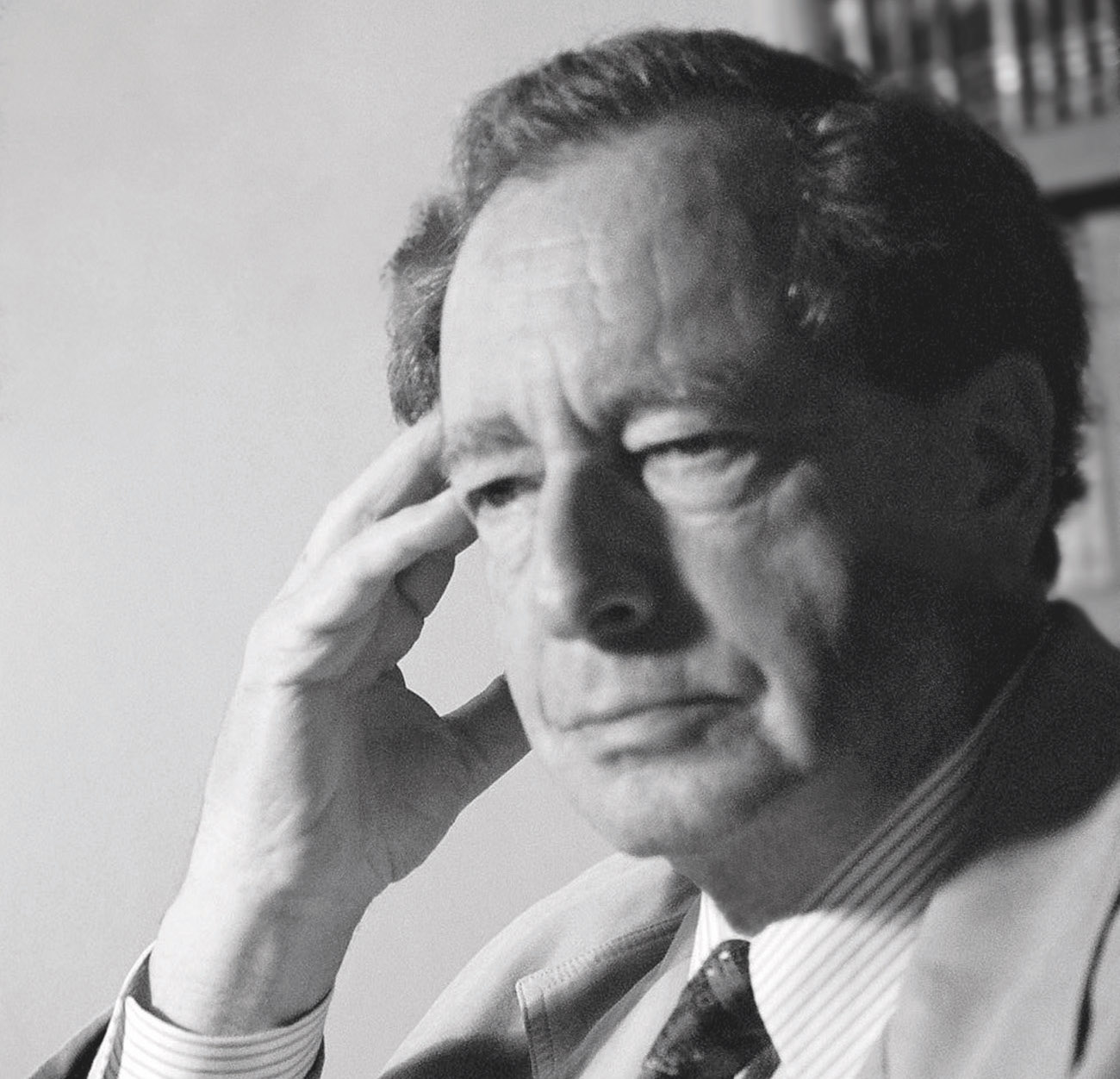

The Catholic physicist, mathematician and philosopher Wolfgang Smith died in July. As a physicist, Smith laid the theoretical foundations for a solution to the re-entry problem explaining how space shuttles can re-enter the atmosphere without burning up. As a mathematician, he pioneered a branch of differential geometry called submersion theory. But perhaps Smith will be remembered most of all for his contribution to the field of science and religion.

Many people view the relationship between science and religion as one of non-overlapping magisteria. According to this view, there is no conflict between science and religion since they deal with entirely different questions. Smith, however, disagreed. In the introduction to his 1998 Templeton Lecture on Christianity and the Natural Sciences, he said: “I believe that the reputed conflict between science and religion does exist, and is in fact far more serious than one tends to think; but, at the same time, I am persuaded that the conflict arises not from science as such but from a penumbra of scientistic beliefs for which in reality there is no scientific support at all … I have no doubt that the ongoing de-Christianisation of Western society is due in large measure to the imposition of the prevailing scientistic worldview.”

The scientistic worldview of which Smith spoke assumes that whatever cannot be mathematically quantified and subjected to scientific investigation has no objective existence. Smith traces it back to the pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus, who in the fifth century BC summed up his theory of physical reality with the saying: “By convention sweet; by convention, bitter; by convention, hot; by convention, cold; by convention, colour; but in reality, atoms and void.”

Democritus was wrong, for in reality we do live in a world full of sound and colour – what Smith referred to as the corporeal world. But when doing physics, we must forget about the corporeal world, and only consider the so-called physical world, a world that deals with things like electrons and protons that are without sound and colour. This is all well and good, for by understanding the world in physical rather than corporeal terms, physicists have made many amazing discoveries, discoveries on which the whole of our technological society depends.

However, serious problems arise when we forget that what the physicist studies is not the whole of reality. Then we become blind to the better half of reality: the corporeal reality that inspires artists, poets and musicians. It is therefore a terrible disease to think that all there is to reality is atoms and the void, that everything comes into existence from the bottom up, and that the higher things we perceive are just things of the mind. But this is a disease that affects not only physicists – it affects most of the intellectual elite of the Western world.

Smith therefore saw it as his mission to address this sickness and show that there is a richer way of understanding reality in which the corporeal world gives rise to the physical world rather than the other way around. This richer understanding of reality was very much shaped by his experience of what he called true religion: true religion comes from above and raises you up whereas false religion comes from below and pulls you down.

Smith was born into a Catholic family, but in his youth he drifted away from the Faith and instead developed an interest in the Vedic religion – he even spent several months in India living alongside some Vedic ascetics. He only reconnected with his Christian roots at the age of 40 when he married a Catholic, but his experience among the Vedic ascetics remained with him.

He used to recall an incident in which he visited the monastery of Padre Pio. Although he didn’t have an opportunity to speak to Padre Pio, he saw him being led across the yard by another priest, and for a moment their eyes locked: an experience Smith described as unforgettable. It was as though he could see in Padre Pio something that transcended his humanity, something divine. He remembered thinking that Padre Pio was in a state of consciousness like that of the Vedic ascetics who had attained the ultimate goal of their religion.

Smith therefore believed that both the Catholic religion and the Vedic religion could lead to union with God, and hence that they are both true religions. Nevertheless, he thought these two religions are fundamentally opposed to one another. For whereas the Catholic religion promises human salvation in our attainment of divine union, in the Vedic religion divine union is attained when all that is human within us is snuffed out. In other words, the Vedic religion offers divine union without human salvation.

Although Smith had the deepest respect for the Vedic ascetics with whom he lived, he couldn’t personally accept the path towards divine union they were taking. Instead, he chose the Christian path: the path that recognises that our corporeal reality can be sanctified and redeemed by Jesus Christ. The path taken by Wolfgang Smith was very much reflected in his philosophy of science and religion. May he rest in peace.

<strong><strong>This article appears in the September 2024 edition of the <em>Catholic Herald</em>. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent and high-calibre counter-cultural and orthodox Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/subscribe/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">HERE</mark></a></strong></strong>.