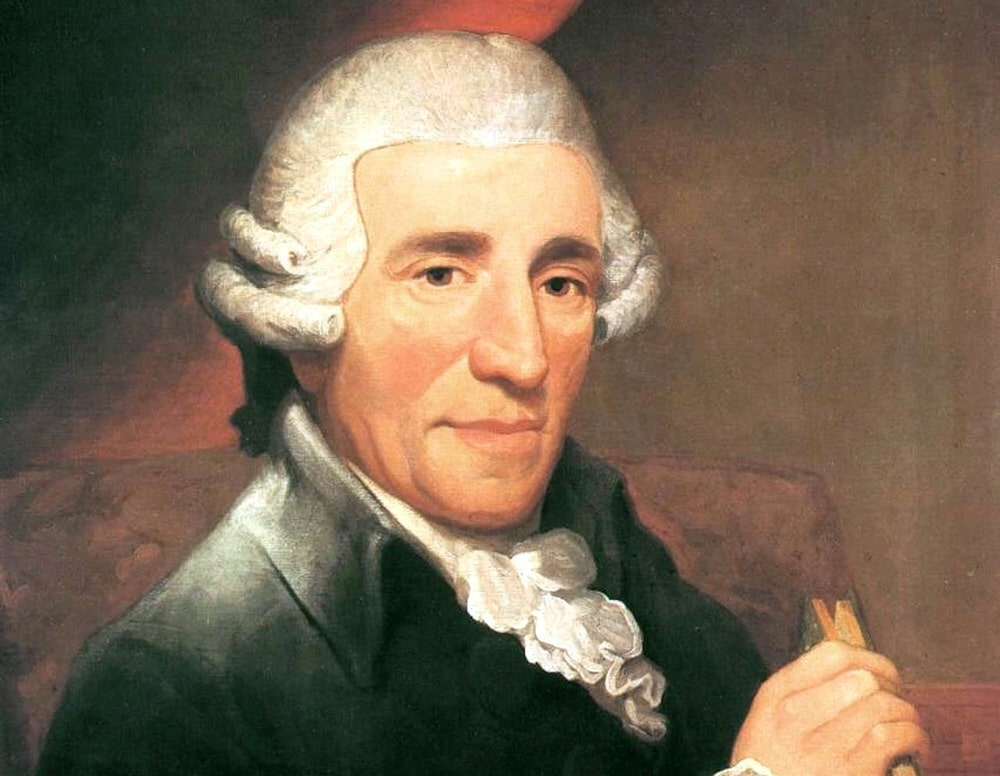

One of history’s greatest Catholic composers, Franz Joseph Haydn’s masses, oratorios and sacred instrumental works are so moving, energising and innovative that he transcended the mere category of musician. In 1785 the English newspaper <em>Gazetteer & New Daily Advertiser</em> called Haydn the “Shakespeare of music”, while an early biographer, Giuseppe Carpani, likened Haydn to Catholic discoverers such as Christopher Columbus or the Venetian painter Tintoretto.

Haydn added a lasting imprint on new genres of music, such as the classical symphony and the string quartet. But even more strikingly, his devoutness radiated in masses which, as the musicologist Guido Adler asserted in 1932, are “artistic expressions of Austrian piety and of the concept of God as dispenser of earthly joy, as modern counter parts, in the rarified atmosphere of musical classicism, of the representations of Christ-Orpheus in one person on the mosaic pavement in Jerusalem and in old paintings in the catacombs”.

Simultaneously of their time and yet eternal, Haydn’s works were the product of a prayer-like process. Another biographer, GA Griesinger, noted that whenever the composer encountered stumbling blocks during his work day he paced his room, rosary in hand, and recited several Hail Marys. New ideas would duly arrive.

Haydn’s mind constantly revolved around different approaches to worship. So he slightly varied the wording of pious inscriptions at the end of his works. When he completed his Opus 20 string quartets, in different musical scores at the end of each one he noted in Latin abbreviations: “To God alone and to each his own” or “Glory be to God in the highest” or “Praise to God and the blessed Virgin Mary with the Holy Spirit.”

These works were nominally secular, but for Haydn, no work was estranged from the sacred. Haydn claimed to friends that his ostensibly abstract symphonies often implicitly spoke of moral principles. One unnamed symphony, said Haydn, portrays “God speaking with an abandoned sinner, pleading with him to reform. But the sinner in his thoughtlessness pays no heed to the admonition.” Listeners have claimed that the slow movements of Haydn’s symphonies Nos 26 and 28 might possibly enact this conversation.

More overtly, the impactful <em>Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross</em>, written for string quartet and other formations, showed how Haydn was able to reach spiritual heights instrumentally. Recordings of the <em>Seven Last Words</em> by the Panocha and Primrose Quartets are exemplary.

Yet in 1903 reforms instituted by Pope Pius X effectively excluded Haydn’s masses, sacred symphonies and chamber pieces from liturgical use. A motu proprio, <em>Tra le Sollecitudini</em>, outlined how classical and baroque compositions must be exchanged for Gregorian chant as models of ecclesiastical music. Pius discouraged music with secular influences, and bar red the use of piano, percussion, strings and other instruments apart from the organ. Haydn’s works were thus removed from church services, even those explicitly written for that function in the form of sacred symphonies as well as settings of the ordinary of the Mass.

The Spanish composer Fernando Sor left a reminiscence of the charm of hearing Haydn’s music in a liturgical context. At age 12 around 1790, Sor arrived at the Santa Maria de Montserrat Abbey as a choir school student. There, he attended the performance of an unspecified Haydn symphony during Mass. Sor recounted: “We were awakened at four o’clock (it was still dark), and we made our way to the church before five o’clock … the Mass was accompanied by a small orchestra consisting of violins, cellos, double basses, bassoons, horns and oboes, all played by children, the oldest of whom cannot have been more than 15 or 16.”

Haydn made no pretence to being a theologian. In 1909, on the centenary of his death, the Austrian church musician Alfred Schnerich complained that six of Haydn’s masses lacked a key article of faith in the Credo. In four mass settings he had omitted the line: “and [I believe] in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only begotten only Son of God”.

This lacuna is glaringly evident in Haydn’s otherwise admirable <em>Missa Brevis </em>in F major (c. 1749), the <em>Missa Brevis Sancti Joannis de Deo</em> (c. 1775), the Nelson Mass (1798) and the <em>Theresa Mass </em>(1799). Some researchers have ascribed this omission to mere forgetfulness; it’s possible, as Haydn was an endearingly flawed mortal.

So convivial was he that as longtime royal conductor for the Esterházy family in Hungary, his first work contract cautioned that Haydn must “abstain from undue familiarity, from eating and drinking, and from other interactions with them so that they will not lose the respect that is his due but on the contrary preserve it.”

This affable, bon vivant element of his personality saddled him with the somewhat condescendingly cozy sobriquet of “Papa Haydn”, contrasting with disapproving views overseas about his Catholicism. Some English Protestants of his day were determined to rescue Haydn from what they saw as a stern, life-denying faith.

In 1785, the aforementioned <em>Gazetteer & New Daily Advertiser</em> suggested that Haydn should be kidnapped from Hungary and smuggled to England. By “devoting his life to the rites and ceremonies of the Roman Catholic Church, which he carries even to superstition”, Haydn has doomed himself, claimed an editorial.

So “aspiring youths” in England were invited to “rescue” Haydn and bring him to Great Britain, the “country for which his music seems to be made”. This caricature of Haydn’s devotion to God was echoed in another English journal, the <em>Morning Herald</em>, in the same year. It described Haydn as “so great a bigot to the ceremonies of religion, that all his leisure moments are continuously engaged in the celebration of Masses, and in the contemplation of purgatory”.

The <em>Morning Herald </em>posited that Haydn’s unhappy home life, wed to a harsh-voiced wife, impelled him to “seek consolation in the bosom of the Church”.

This uncomprehending mockery does not correspond with a composer who in later life chose a simple daily supper of bread and Tokay wine, emulating the Last Supper; nor one who told his biographer, Carpani, that when he was writing the majestic oratorio The Creation, he “felt so imbued with religious feelings that before I began work, I turned to God with passionate prayer”.

As might be expected, <em>The Catholic Encyclopedia</em> (1910) argued that banning Haydn’s ecclesiastical music from church ceremonies, including 14 Masses, one <em>Stabat Mater</em>, two <em>Te Deums</em> and 34 offertories and anthems, made sense because of, among other reasons, the “operatic character of the music itself”.

The pendulum has since swung back, and what sounded operatic in 1910 once more inspires worshippers just over a century later. Without casting any opprobrium on the splendour of Gregorian chant, the Church surely benefits from a more inclusive approach to the work of Haydn and his most accomplished contemporaries.

<em>Benjamin Ivry is a writer, broadcaster and translator.</em>

<strong><strong>This article originally appeared in the April 2024 issue of the <em>Catholic Herald</em>. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent and high-calibre counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click</strong> <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/easter-24/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">here</mark></a>.</strong>