Unlike the British Empire, the sun never truly seems to set on the Silk Road. It doesn’t matter how often that path is travelled, romance is always around the corner. Somehow it’s a different matter when President Xi Jinping puts on his hard hat and gets digging for the press on his Belt and Road Initiative. Silk still flows out of China and the West still sends its least affordable luxuries eastwards.

The British Museum has managed to add some of that commercial grit to the undulating sands of time. "Silk Roads" is dramatic in places and globalised throughout. The curators have even managed to squeeze in the wastes of northern Europe alongside the wastes of Central Asia.

The different routes of the Silk Road are of special interest to Islamic-art historians although the British Museum has diversified as much as it can. Most of the lands through which the various roads meandered became Muslim. Nestorian Christians were there, too, several centuries after Christ. Later Catholic missionaries in China were distressed to find these heretical Christians had got there first and received the Tang emperor’s approval.

Essentially, though, trade has always been more central to Islam than to most faiths, especially Christianity. So, be prepared for plenty of Islamophilia at this exhibition. Also, get ready for maps. The cartography department has been busy ensuring that visitors can navigate their way through the many complex routes. A large number of these were actually maritime. "Sea roads" are on the maps, albeit without the same artefact opportunities as dry land.

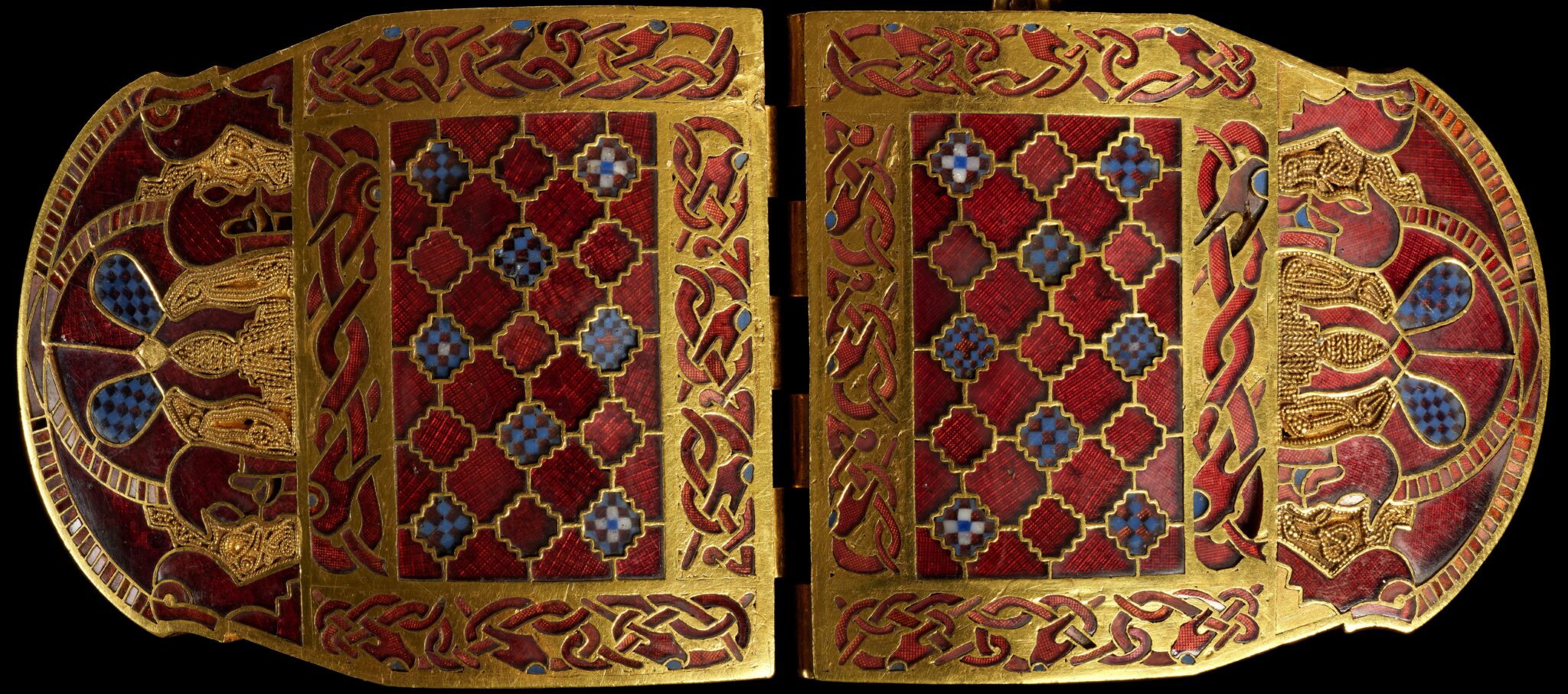

It’s an exhibition about people, places and faith, but it’s also filled with stuff. Having a geographical spread from East Asia to East Anglia is a fair excuse for bringing out everything that deserves more attention than it would get in the British Museum’s permanent display. Top of that list is the most thrilling discovery – for me at least – in an exhibition on the Silk Road(s).

One of the earliest representations of Christ’s crucifixion is on an ivory box from 5th-century Rome. Yes, this curatorial road leads there. The usual home of this tiny masterpiece is a desolate corner in the shadow of the Sutton Hoo treasures. Of course the latter gets all the attention, plus a first-rate film starring Ralph Fiennes. At least on this occasion the crucifixion brings in the crowds.

The reason for the panels’ presence is a bit vague; something to do with the extinction of North African elephants. More astonishingly vague is the description of the central event in Christian iconography: “exquisitely carved panels depicting events before and after Christ’s resurrection.” The ivory itself tells the story eloquently: Christ on a cross, Judas on a tree.

All of this is a diversion from the route of the exhibition storyline. The first thing is that it’s about much more than silk. Other imports/exports appear to have taken up more camel haulage space. In fact, there’s very little silk at all on display. It’s not a durable material, certainly when compared with rock, glass, ceramic, ivory, wood or almost anything else on show here.

One of the most visible and intact silk items is from Egypt, circa AD 600-900, when it was part of the Byzantine Empire. The arid lands of Central Asia are famed for preserving all sorts of wonders for posterity, including people. The possibly Western European mummies found in Xinjiang have not been brought to Bloomsbury, and they wore animal skins rather than silk anyway.

The point of the mummies is made by the exhibition using the word Eurasia liberally. It’s out with the phoney old divisions between Europe and Asia, and in with the reality of one huge multicultural landmass, filled with eager traders by the look of it.

When you take silk out of the picture, the exhibition could end up being called “Roads”. A lot less magical but actually in keeping with the look of the display. With a profusion of place names hanging overhead, it feels like we are travelling with Captain Kirk at Warp – or maybe Weft – Speed. You can get from Cairo to Rome in about a minute, treading a careful path through the information-hungry crowd that gathers at every caption.

AI interactivity is all very well, but most visitors who have paid for the privilege seem to prefer the visual stimulation of chemical ink on a felled tree. Paper, by the way, was another by-product of the Silk Road, disseminated through the Islamic world before reaching Western Europe.

Buddhist manuscripts and paintings are essential to this exhibition, with the Dunhuang caves in northwestern China at its core. The world’s oldest printed paper book, the Diamond Sutra from 868 AD, can be seen down a different road at the British Library, which is holding a rival (or perhaps complementary) exhibition on the wonders of Dunhuang.

The objects on display at the British Museum are less about writing and more about art in the round. Along the way, the curators weave in Buddhism, Islam and Christianity. There is something of a detour around the oldest living religion – Hinduism – while Judaism does make a showing. It’s fortunate that devotional art pays the biggest visual dividends.

The timeline is mostly AD 500-1000, which was prime time for spiritual expressiveness. The output is as diverse as the religions; the effect is impressive and sometimes sad. The Bamiyan Buddhas, for example, are represented in the form of a reduced clay figure close to a photo of the much vaster versions destroyed by the Taliban.

Iconoclasm has affected countless cultures over the centuries. Much of what has been left from the Silk Roads era is in the hands of the British Museum and similar institutions. Better cared for than by Afghan warlords, many of the finest works have been brought out for this exhibition. The list of lenders is almost as global as the display itself, with the participation of museums from Tokyo to Tashkent and Southend. There’s a massive amount to see, and all superbly illuminated. Well worth a visit, more so if you have no special interest in silk or roads.

<em>Photo: Gold shoulder clasps with garnets and glass. (Credit: <a href="https://www.britishmuseum.org/exhibitions/silk-roads"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">British Museum</mark></a>.)</em>