Last week, surgeons in England hailed the “astonishing” medical breakthrough by which a 36-year-old woman became the first in this country to give birth following a womb transplant.

The <em>Guardian</em> reported that Grace Davidson, who has <mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color"><a href="https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/mayer-rokitansky-kuster-hauser-syndrome/">Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome</a></mark>, a condition in which the womb never fully develops, had her baby, Amy Isabel, by caesarean section. Amy Isabel is named after Grace’s sister Amy Purdie who donated her womb two years ago in an 8-hour operation, and also after Isabel Quiroga, a surgeon who helped perfect the transplant technique.

Professor Richard Smith, who led the research team on womb transplantation and was present at the birth, said, “There’s been a lot of tears shed by all of us in this process – really quite emotional, for sure. It is really something…It was overwhelming actually, it remains overwhelming. It’s fantastic.”

These reactions are, at least in some sense, appropriate to the birth of a baby – though <a href="https://thecatholicherald.com/first-uk-baby-born-using-transplanted-womb/"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">the intoxicated tone</mark></a> may have more to do with the success of the process leading up to the event. The tacit assumption of both surgeons and the media is that the “end” – the birth of a baby after such serious infertility – morally elevates the “means” used to achieve this end. Sarah Norcross, director of The Progress Educational Trust (PET), announced that:

“It has been little more than a decade since the world's first ever live birth following a womb transplant, and now the UK has its own womb transplant success story. This news will give hope to other women who wish to carry a pregnancy, but who have no uterus of their own.”

Such responses to advances in reproductive technology help form the attitudes of readers as the relentlessly positive headlines accompany photographs of happy families together with the surgeons who made their dreams come true.

But what are we to make of the “means” used in this case? What might their lauded use betoken?

Technological advances can bring with them significant rewards yet also very real losses, which an impatient and inattentive culture is liable to forget. For in their promise of an increase in our own sovereignty – even over issues of reproduction and maternity – they are liable to bring with them new forms of enslavement of the self.

We need particular caution when it comes to advances in repro-technology which touch on “core” meanings of our bodies – the very basis for our biological family ties.

What, then, do womb transplants involve? A womb donor, whether living or “post-mortem”, must be found. The language of “donor” is familiar to us from standard organ donation and relates to the idea of a “gift". Donating certain body parts after death, for example, can be praiseworthy, albeit with strong caveats concerning diagnosis of death (an issue also relevant to womb transplants which sometimes use what are known as “beating heart cadavers”).

As regards live donation, its licit practice involves, among other things, conditions regarding what we can and can’t do when it comes to compromising healthy functioning. The welfare of donors must be respected and functional mutilation avoided.

Note that the positive term “donor” is now also routinely applied to those “donating” sperm or ova, for procedures which make such donors fathers or mothers in the most fragmentary sense of these noble roles. The donor disavows in advance all desire for gestational and social parenthood, while for the would-be parent the body-language of one-flesh spousal union gives way to a literal process of production.

The difference between organ donation and gamete donation will be evident to anyone aware of the special nature of our reproductive powers, which carry a unique meaning not shared by our other bodily functions.

In between these two uses of the term “donation” we may place the “donation” of one woman’s uterus to another woman. The uterus, unlike the sperm or ovum, does not contribute material to the <em>creation </em>of the new human being. Nonetheless, it is very much part of a woman’s reproductive system, not only during the nurture of the baby to term, but during the baby’s conception if this happens naturally.

Following intercourse, sperm passes through the womb to the fallopian tube where fertilisation may occur. The womb is not quite like the vagina, which is immediately involved in intercourse, but nonetheless it is intimately connected with the marital act. It is not just for nurturing babies, but is part of the woman’s whole way of receiving her husband and the “gift” of his reproductive material which may mingle with her own.

The womb Grace Davidson accepted from her sister Amy Purdie was undeniably an intimate part of her sister’s marital life – even if neither sister saw things that way and the donation was generously meant and gratefully received. The womb was at very least the “antechamber” to the place where Amy most likely conceived her own children (a child can be conceived in the uterus itself but this is rare).

If we baulk at the idea of transplanting a vagina, which is surely meant for marital expression of the original woman alone, should we accept a womb transplant, even in principle? We might remember here the reflections of Pope Pius XII and subsequent Church pronouncements which, while positive about transplantation generally, make exceptions both for the brain and for reproductive material, given the central importance of both to our specific identity as embodied persons.

To return to healthy functioning, another concern of Pius XII, a donor’s health must always be respected. In the case of womb transplants, if the donor is premenopausal, as was the case with Amy Purdie, she will, of course, be made permanently infertile by the operation. Besides the certainty of infertility, there are risks to the donor which should not be underestimated.

There were risks for Grace Davidson too, who had to undergo multiple procedures and immunosuppressive therapy which still continues and which also carried some risk to her baby. We should remember that womb donation is not a life-saving donation like, say, a kidney: infertility is a heavy cross to bear but is not life-endangering. And, crucially, sex-related organs like the womb are a central part of our embodied nature, carrying a marital meaning which, in several ways, militates against transfer.

Due to the fact the transplanted womb is unconnected to fallopian tubes, for fear of ectopic pregnancy, conception cannot be achieved by intercourse and any birth will involve IVF embryos. Here we are on sadly familiar territory. IVF replaces the marital act with a production process for the creation of new human beings – in Grace Davidson’s case, seven embryos – outside the mother’s body. Such a procedure places the parents in a position not of receivers of a gift arising from an act of mutual bodily self-giving, but of producers manipulating material or having it manipulated on their behalf. That is the way to produce objects, not human beings equal to ourselves.

The new human being’s very dignity requires that he or she be brought into the world in a manner which pays tribute to that dignity – in other words, through an act which is truly marital and unitive because it is procreative in kind. Moreover, all too often, those created in the manner of products are – at least as embryos – treated accordingly: what will happen to any remaining embryos, once Grace has had the second pregnancy she wishes to have?

Womb transplants involve, then, hugely complex surgery and other risky interventions, permanent sterilisation of the premenopausal live donor and the use of IVF with its usual production and freezing of multiple embryos. There is no respect here for the true meaning of the body and of marital acts and of parenthood. We are embodied beings, and our bodies are not “mere matter” to manipulate – rather, they have a meaning which cannot be ignored. Even for the very good ultimate end of a child, not all means may be pursued.

The striving for sovereignty over ourselves results in treating ourselves too much as manipulable material, down to our very masculinity and femininity. The <a href="https://thecatholicherald.com/uk-supreme-court-rules-trans-women-arent-legally-women/"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">current debates over transgender issues have underlined</mark></a>, in a most drastic way, how far this error has taken us and it comes as no surprise that some are already talking of womb transplants as a future option for men who identify as women.

With the prior hollowing out of respect for sex and parenthood through contraception, abortion, IVF and surrogacy, the idea of transferability of the womb, an organ central to motherhood, becomes all the more thinkable. But by treating our reproductive parts as alienable from ourselves – something we can gift to other people to have their families – we lose hold of a sense of the meaning of our sexual/reproductive powers and their connections to our maternity and paternity.

The womb has its own nature, which is part of human nature and therefore has a moral meaning. Only a society which, enthralled by technological advances, has lost sight of reverence for the body and its normative pull on our moral sensibilities can regard last week’s news as uncomplicatedly good – good not only in terms of the good "end" achieved of new life, but also in the "means" through which that end was brought about.

For the very dignity in which new human life partakes requires respect for the dignity which permeates marriage and the marital act by which men and women best prepare for, conceive and nurture the gift of a child.

<a href="https://thecatholicherald.com/the-chilling-story-of-how-eugenic-theory-and-later-ivf-was-pioneered-in-britain/"><strong><em><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">RELATED: The chilling story of how eugenic theory, and later IVF, was pioneered in Britain</mark></em></strong></a>

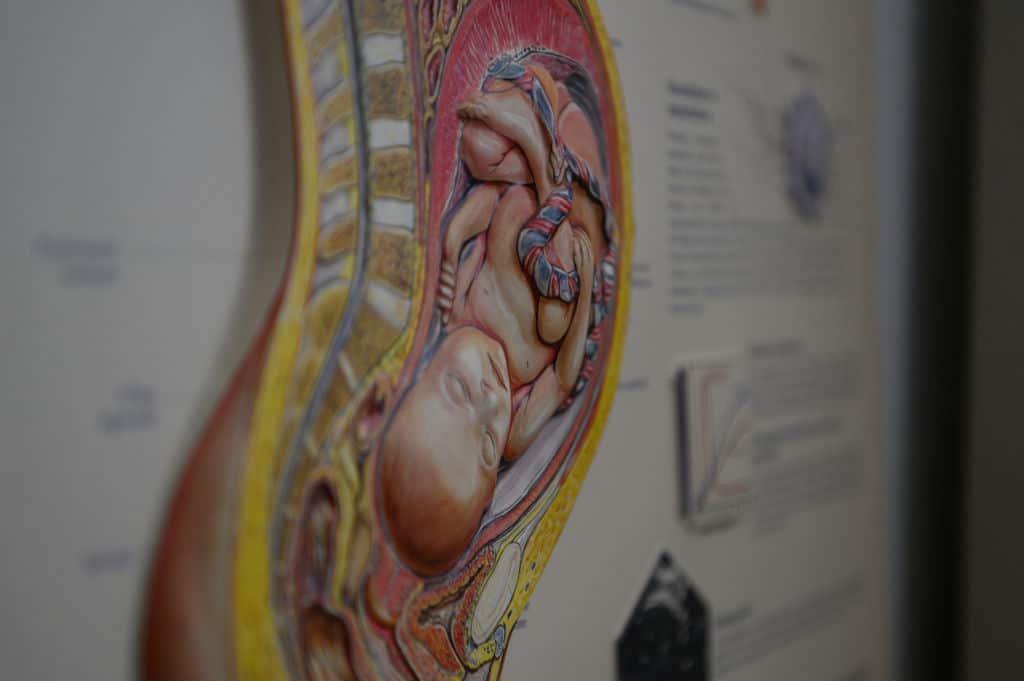

<em>Photo: A representation of a 3D anatomy of a baby in the womb of a pregnant women displayed on a wall at a hospital ward in Strasbourg, France, 1 February 2025. (Photo by ELSA RANCEL/AFP via Getty Images.)</em>

<em>Anthony McCarthy is director of the Bios Centre (<a href="http://www.bioscentre.org/"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">www.bioscentre.org</mark></a>).</em>