Despite being a former French colony, Cambodia has no cathedrals. The Khmer Rouge destroyed most church buildings soon after seizing control of the country on this day 50 years ago in April 1975. It's a salutary thought, to say the least, this Maundy Thursday.

During the nightmarish Khmer Rouge reign, which lasted just under four years, most Catholics either perished or fled to other countries – typically neighbouring Vietnam, the ancestral homeland of many of Cambodia's faithful.

Catholics currently account for just one-fifth of 1 per cent of Cambodia's overall population of 18 million. Catholicism first arrived in Cambodia in the mid-1550s by way of Portuguese Jesuits. Such attempts to evangelise the native Cambodians (often called “Khmer", the name of both the main language and ethnic group) were a failure.

“Cambodia was considered as a country which did not respond to the Gospel,” says Fr. Vincent Sénéchal of the Paris Foreign Missions Society (<em>Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris</em>/MEP). He served in Cambodia as a lay missionary from 1995 to 1997 and as a missionary priest from 2007 to 2016.

Historically, Khmers have been far more resistant to Catholicism than the Vietnamese. Catholic missionaries “have tried to answer many times” as to why this is so, says Fr. Luca Bolelli, of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions (PIME), who left Cambodia in September 2019 after serving there for 12 years.

Not until 1957, four centuries after Catholicism's arrival, did the first Khmer priest receive ordination. Soon after the Church finally showed some degree of momentum, the nation descended into widespread internecine conflict, and its countryside met with some of the most intense bombing this world has ever seen.

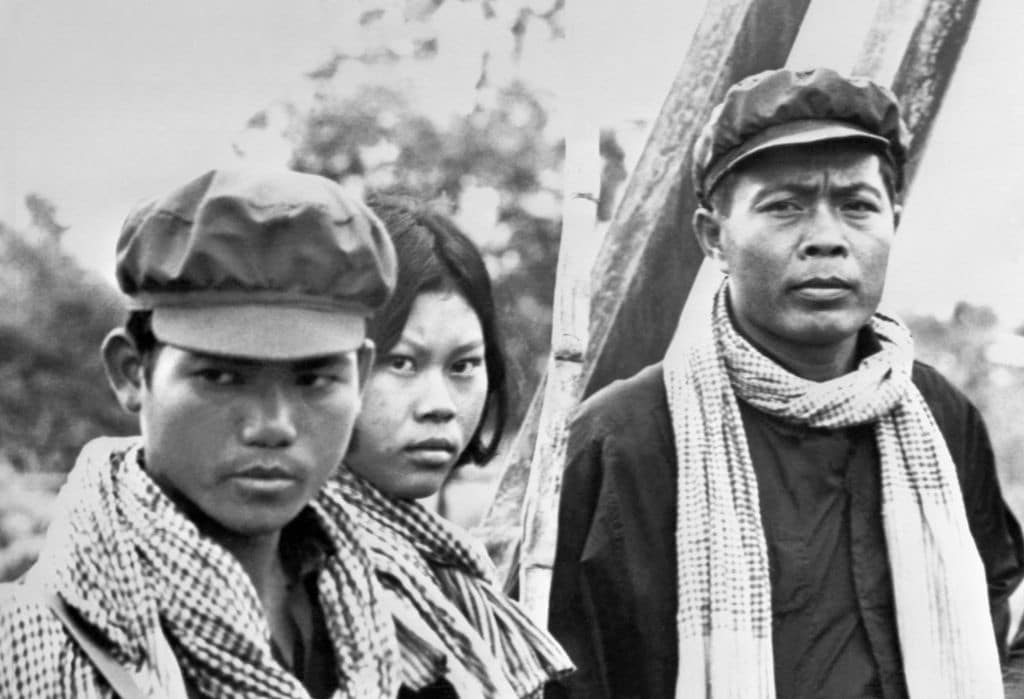

Then, on 17 April 1975, a shadowy group of rebels known as the Khmer Rouge took control of the capital city, Phnom Penh, and proceeded to forcibly evacuate its 2 million inhabitants, sending them to forced labour camps in rural locations.

Instituting “Year Zero", the Khmer Rouge and its secretive leader Pol Pot sought to establish an agrarian utopia free of any foreign influence, which he perceived as corrupt. As part of the purification process, he tried to eradicate music, dance, art, books, holidays and, of course, religion.

Pushing totalitarianism to a new extreme, about 1.7 million people in Cambodia would perish through murder, starvation or overexertion during forced labor, according to Yale University's Cambodian Genocide Program. To put this number in perspective, Cambodia's population circa 1975 was between 7 and 8 million people.

The Khmer Rouge period might have lasted far longer, but the group's homicidal paranoia led to the catastrophically foolish decision to launch attacks on the neighbouring Vietnamese, who had a far larger and superior military. Vietnam responded by invading Cambodia on Christmas Day 1978. Many high-ranking Khmer Rouge soon fled into the dense jungles along the border with Thailand.

Though few, if anyone, regretted the Khmer Rouge's absence, there was scant reason to celebrate, as the Cambodian-Vietnamese War was now underway. And it would last for over a decade, terminating in late 1989. Not until Easter Sunday 1990 were Catholics in Cambodia able to come together as a group and pray publicly. It was high time for a resurrection.

Even though Cambodia was decimated, Fr. Bolelli points out how the Church retained a vital, albeit intangible, foundation. “Faith was kept alive among families and in the hearts of the people even though buildings were destroyed and public expressions were denied,” he says.

The endurance of such faith “had a strong impact on the missionaries who came back to Cambodia” once the country finally reopened to the outside world.

Fr. Bolelli recalls how Bishop Yves Ramousse (the former Apostolic Vicar of Phnom Penh who died in 2021) and “other old French missionaries” used to say, “The Church survived in the hearts of the people.” Fr. Bolelli explains, “That is why they didn't want to restart the Church by rebuilding churches or schools.” Rather, they restarted by “visiting Christians” and “collecting them in synods". He adds how they also sought to “Khmerise” the Church, which had previously been “more French-Vietnamese than Khmer".

Fr. Sénéchal describes the churches built after the Khmer Rouge era as “small and humble". He adds that only in more recent years have Cambodian communities begun to construct more elaborate church buildings.

As the <em>Phnom Penh Post </em>newspaper has stated, the Catholic Church in Cambodia “wields influence beyond the number of faithful". Fr. Sénéchal says the Church is involved with many charity programs related to education and health care. He credits the Fathers and Sisters of Don Bosco for their successful educational and professional training programs, and also credits Caritas Cambodia with having done “an amazing job for many years now".

Fr. Bolelli relates that the Church, aside from assisting the ill and impoverished, has opened schools, provided scholarships and supported education from kindergarten to university.

Fr. Sénéchal adds that Jesuits in particular have been at the forefront of treating Cambodians maimed and disabled by mines. The wars are over, but life-changing danger lurks just a few feet off the beaten path throughout much of the countryside. Numerous landmines, neglected for decades, remain ready as ever to erupt beneath anyone who makes an errant step.

“The Cambodian people's resilience is remarkable,” says Fr. Sénéchal, but adds that at times “the trauma is still visible". Basically any Cambodian over age 50 knows a level of terror and hardship that the vast portion of humanity could barely imagine.

Cambodia is a very youthful country now, with a median age around 25 years. This means the majority of Cambodians had no experience with the Khmer Rouge. But they have likely seen significant technological progress.

The country saw an economic boom from 2010 until the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, as Fr. Bolelli points out. He tells how, when he visited an isolated Catholic Cambodian village on the Mekong River in late 2009, it had “no roads, no electricity, no water or internet". Ten years later, just before he left Cambodia, that same village had seen drastic change. “The road was asphalted, a huge bridge was under construction, each house had electricity and water, and internet and smartphones were part of daily life,” he says.

Fr. Sénéchal agrees that “the standard of living has significantly improved” in recent decades. Aside from Church programs, he points out that secular international organisations have made solid contributions. Arguably most encouraging of all, though, is that “Cambodians themselves have set up development programs” and boosted their nation's economy, says Fr. Sénéchal, who adds that “today we can see the rise of a middle class".

The most dramatic signs of economic progress have taken place in Phnom Penh, now home to one of the world's most rapidly changing skylines. Each of the city's 20 tallest buildings was built within the last dozen years.

New Catholic churches are appearing as well. And while they have far less stature than the skyscrapers, they span a far wider geographical range. Fr. Bolelli says that a church recently surfaced in the far eastern region of Mondulkiri, the most sparsely populated of the country's 25 provinces.

The trajectory seems positive for a country that had to rise from the ashes of Year Zero. In its small Catholic community, faith survived amid the destruction of all else.

<em>Photo: Khmer Rouge Colonel Vichai (right) poses with his wife and his deputy at the Cambodian-Thai border in Poipet, 06 May 1975. The Khmer Rouge entered Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975 before establishing their Democratic Kampuchea (DK) government. (Photo by -/AFP via Getty Images.)</em>

<em>Ray Cavanaugh is a Massachusetts native who enjoys writing about subjects far removed from Massachusetts. He is interested in the Catholic history of countries where Catholics are a small minority.</em>