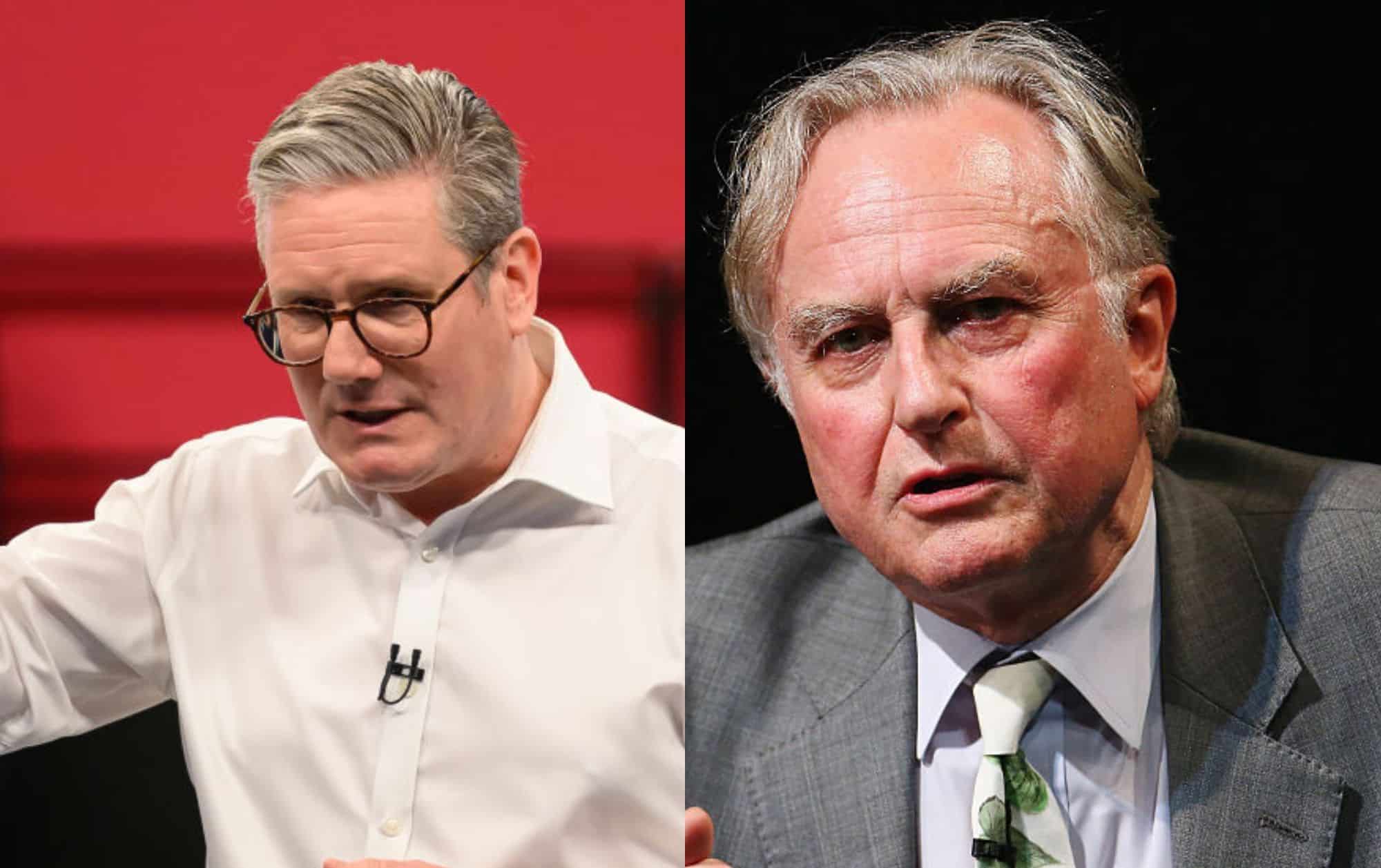

This month's magazine <a href="https://x.com/CatholicHerald/status/1785726985911534045"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">cover issue</mark></a> is the prospect of Britain’s first avowedly atheist prime minister after the UK general election on 4 July. Sir Keir Starmer, the Labour leader, would not be the first unbeliever as head of government; rather, as Paul Goodman points out, he would be the first to admit as much openly. We already have the first non-Christian Prime Minister with Rishi Sunak, who is a practising Hindu. Yet it is still a jolt to realise that unbelief is so prevalent in politics as to be unremarkable to the electorate. Britain has changed, obviously. In 2021 the census findings revealed that less than half the population, 46 per cent, identified as Christian, and this was far more the case among the young. The situation is not primarily attributable to immigration from non-Christian countries, though this is a factor; it is the falling away of a generation that a couple of decades ago would mostly have thought of itself as Christian. Sir Keir, then, is representative of contemporary Britain in his absence of faith and his willingness to admit it.

And yet, as Lord Goodman says, Sir Keir is familiar with religion as a social influence. Lady Starmer is Jewish, and the family celebrates a Sabbath meal every week; insofar as he practices a religion, it is the Jewish faith. Yet he himself comes from a background for which the best description is that useful catchphrase, “cultural Christian”. In the small town from which he comes in Surrey the local Anglican church, which his disabled mother attended, was a centre for social and community life; his father was militantly atheist yet on friendly terms with the vicar. This is a background which was once the British norm.

The marginalisaton of that taken-for-granted faith has been a loss, socially as well as spiritually. If Britain is a more atomised, more individualistic, lonelier society, one reason is that people no longer attend a church – although many others at tend a mosque.

So we are left with that ambiguous thing, cultural Christianity, which means those whose family have been Christian, who are vaguely familiar with Bible stories, who like Christian art and broadly identify with a Christian ethos. Of these, the most famous recent example is Richard Dawkins, a proselytising atheist who now says he is happy to call himself a cultural Christian, values the literary aspect of the Bible and is glad to live in a culturally Christian country – yet cannot profess a word of the Creed.

Many cultural Christians, like Prof Dawkins and indeed the Prime Minister himself, went to Anglican schools; one reason why Rishi Sunak is perfectly at home reading from the Christian scriptures in services on national occasions is that he attended Winchester College. But the number of schools where pupils attend chapel and learn scripture as these men did is now very small.

Cultural Christianity is not a faith; it is the residue or imprint of faith. We shall see how long people continue to feel an affinity with Christianity without any encounter with its practice or any knowledge of its beliefs. Those whose parents went to church, like Sir Keir’s mother, will have a knowledge of faith, but that tenuous connection can hardly survive into the next generation. We should be clear what that loss entails.

Christianity is at the root of the ethical system of the West and of those countries that embraced Christianity; the very concept of individual human dignity and the liberal project derives from the faith. The historian Tom Holland makes this clear in his book <em>Dominion</em>. As another historian, Sir Larry Siedentop, explains in <em>Inventing the Individual</em>, the roots of individualism are firmly grounded in Christianity. If the faith that produced these things withers, individual human dignity may ultimately wither too.

Catholics can ensure that Christianity is not wholly marginalised. If Catholic schools do their job properly in forming pupils in the knowledge and love of God, they will ensure that there remains a cohort of believers to challenge the secular consensus. And where the faith is practised wholeheartedly, it can still attract converts. Cultural Christianity is a dead thing, but the Church in Britain, though smaller than it was, is very much alive.

<strong><strong>This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of the <em>Catholic Herald</em>. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent and high-calibre counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click</strong> <a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/subscribe/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">here</mark></a>.</strong>