<em>Liberty over London Bridge: A History of the People of Southwark</em> by Margaret Willes

Yale University Press, £20, 304 pages

The dead are interesting, even fascinating, but never nearly so much as the living. Long strangled by a stultifying confederacy of German bombs, English planners and international finance, the City of London is dead. Across London Bridge, however, is a place very much alive: the Borough of Southwark. Its people are the subject of an admirable centuries-spanning chronicle by Margaret Willes, previously known for her well-received history of the Square Mile relayed through the prism of the churchyard of St Paul’s Cathedral.

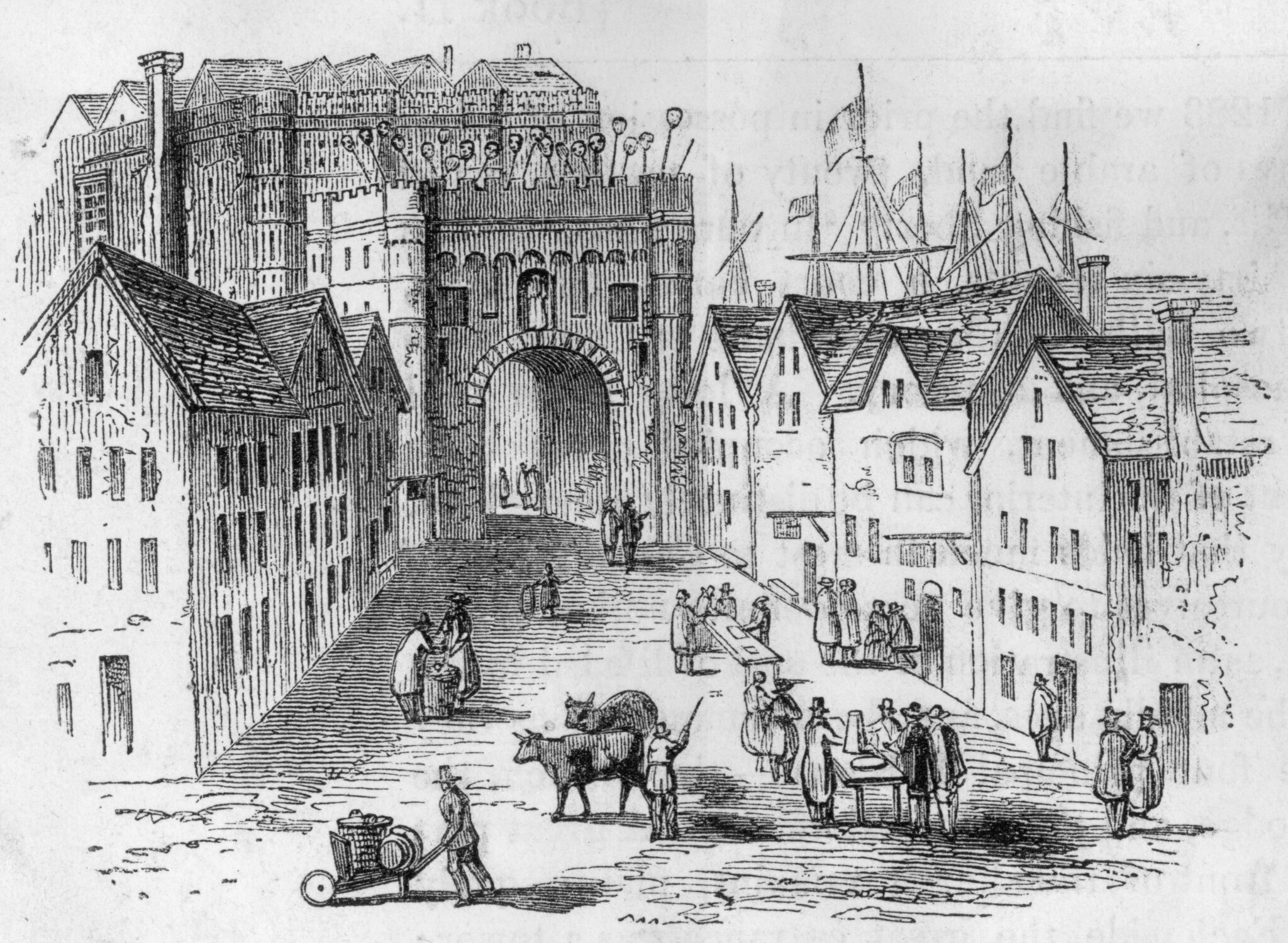

In Liberty Over London Bridge the glories of Southwark are borne in splendid procession. Some are already familiar, not just to those of us who live here: Shakespeare and his plays at the Globe or Chaucer’s pilgrims setting off to Canterbury from the Tabard. Others are lesser-known but worthy of examination. John Taylor, the sailor and Thames waterman, was one of the most popular and widely-read poets of the Stuart age but sank into virtual obscurity.

When I nip in to Choral Evensong at St Mary Overie (that’s Southwark Cathedral to our Anglican friends) I usually find a place near the polychromatic restored tomb of John Gower. Out of my disgraceful ignorance I had presumed Gower was some uninteresting rich merchant. Willes enlightens my darkness by showing him to be a lawman of note and a poet of importance, as well as an old drinking chum of Geoffrey Chaucer.

Bear-baiting, cock pits, theatres, inns and hostelries, breweries and, above all, brothels – they thrived in the Borough. Not for nothing has our little bailiwick earned the moniker of “the most disreputable quarter of London”. Repeated attempts by the City to expand its authority across the Thames and rein in the raucous revelry were, blessedly, all repelled and defeated. The rich tapestry of Southwark’s life, from the seedy to the refined, are depicted in their fullness here.

Willes is excellent on the history of the Augustinian priory of Southwark and the trials and tribulations it has gone through: nationalised by Thomas Cromwell, sold to the locals, its nave turned into a parish church, the retrochoir housing a congregation of French Protestant “Strangers”, with bits of it rented out to bakers, printers and others over the centuries. Its transformation into Southwark’s Anglican cathedral in 1905 gave the former priory a significance it lacked during its centuries as the parish church of St Saviour.

The author subscribes to a narrative of history that is terribly old-fashioned and much deprecated these days: that of the educated and confident 1950s English Establishment. This perspective’s current rarity makes the take almost refreshing, while reminding us also of its limits. For example, once the Reformation hits, anything Catholic is Roman.

Mary I, Willes assures us, was “determined to return England to the Church of Rome”. One might more accurately say to the traditional faith of the English for a millennium. This attitude seems even to have infected her indexer: You won’t find “Catholicism” in the listings but you will find “Roman Catholics”. That lot! Willes’s account of the Williamite invasion of 1688 is similarly old hat.

Any reader looking to follow up on the Herald’s coverage last year of the 175th anniversary of Southwark’s Catholic cathedral for an insightful account of the importance of this building, its design and its people to Southwark, London, and the nation will be disappointed. St George’s gets the short shrift of a single brief mention, dismissed as being “established in 1852 as a cathedral for the Irish community”.

The Catholic parish dates back to the 1780s, the building was first completed in 1848, and it was raised to cathedral status in 1852. That the first great post-Reformation Catholic church building in the capital of the United Kingdom – and the British Empire – was raised here in Southwark interests the author little, and in the whole book Pugin is only mentioned for critiquing the 1840s nave of St Saviour’s.

Pugin is lucky: Sir Ninian Comper, whose tasteful refinements so augmented the Anglican Cathedral, gets no mention at all. Willes does, helpfully, give a succinctly informative overview of the Church of England bishop Mervyn Stockwood and the broad liberal Southwark school of theology or “South Bank religion” which flourished (up to a point) in the 1960s and 1970s.

These few demerits are mere quibbles overall. For those who have not had the great privilege of living in, knowing and loving the ancient borough of Southwark, Willes has provided an excellent and very welcome introduction to this lively and story-sodden quarter.

<em>Andrew Cusack is Metropolitan Crucifer to the Archbishop of Southwark</em>

<strong><strong><strong><strong>This article originally appeared in the May 2024 issue of the <em>Catholic Herald</em>. To subscribe to our award-winning, thought-provoking magazine and have independent and high-calibre counter-cultural Catholic journalism delivered to your door anywhere in the world click</strong> <mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color"><a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/subscribe/?swcfpc=1">h</a></mark><a href="https://catholicherald.co.uk/subscribe/?swcfpc=1"><mark style="background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0)" class="has-inline-color has-vivid-cyan-blue-color">ere</mark></a>.</strong></strong></strong>